| / WHISKY |

Enjoying large each spring and well,

As Nature gave them me

The Humble Petition of Bruar Water

Robert Burns

The flowing stream is featured prominently on Ballantine's coat of arms, not simply because water is a vital ingredient of whisky, but because it also forms such an important part of the Scottish climate.

Visit any region in Scotland and you'll encounter a weather expression which sounds vaguely similar, only the place names have been changed. In Ayreshire, for instance, they say: 'If you can look across the Firth of Clyde and see the Isle of Arran clearly, it's going to rain. If you can't see it clearly, it's raining already.'

Soft, gentle rain is something of a Scottish speciality. 'Scotch mist', as it is known, is caught and filtered by rocks as old as time to re-emerge in springs and mountain streams which fuel a worldwide whisky industry.

Just as malt whisky varies in style and flavour from region to region, the character and nature of water changes - peat brown in some parts, crystal clear in others - influencing whisky's subtle character.

This is illustrated by water expert John Hamilton, who first founded the Highland Spring water company and, in 1992, the Gleneagles Spring Waters Company in the heart of Scotland's golfing country. The Gleneagles Springs, which have a potential to yield 400 tons of water per hour, enough to supply the whole UK bottled water market, is a subsidiary of Ballantine's parent company, Allied Domecq.

'In the days when I founded the Highland Spring water company, there were two springs within 50 metres of each other,' John says. 'One tasted fine, the other caught slightly in the back of the throat, which is a sign of magnesium. Here in Gleneagles, we have two springs a kilometre apart, which are completely different. One is rich in bicarbonates, the other 100 per cent natural water.'

Because of this unpredictable ability to vary dramatically within a small area, water is a commodity highly prized among distillers. An outstanding supply running to a distillery makes a valuable contribution to a fine whisky, from germinating the barley if it does its own malting, to the essential processes of mashing, fermentation and distilling.

Aside from its essential contribution, water exerts a subtle flavour influence on whisky from grain to glass, which is why sources are jealously guarded and ownership secured by deed and contract.

Laphroaig's peat-brown source, for example, was considered almost sacred and so closely linked to the essential character of the malt that nothing less would suffice. Several thousand years ago, long before distilling, the Celts acknowledged the sacred nature of the site by erecting a 14-foot standing stone at Cnoc Mor, where Laphroaig's water collects in a secluded hollow on Islay.

An enormous row broke out in 1907 over the water supply to Laphroaig. At the time, the distillery was run by two sisters, Mrs William Hunter and Miss Katherine Johnston, who decided that the company agent, Mr Mackie, was not giving Laphroaig his fullest attention. They fired Mackie, who flew into a rage and ordered his men to dam Laphroaig's precious supply with stones, reducing the stream to a trickle and bringing production to a halt.

Islay is criss-crossed by fast-flowing streams and, in theory, a lade could have been dug to an alternative supply almost anywhere. But Mackie's action was tantamount to declaring war. A long court battle ensued which ended with the agent being ordered to restore the flow of water from the natural basin in the hills.

In a fit of pique, Mackie decided to put Laphroaig out of business by setting up a rival distillery, just a mile away. He enticed Laphroaig's brewer to work for him, built identical stills and drew water from an adjoining source. But such is the mystery inherent in whisky-making and, in particular, the complex hydro-geology of Islay, that the resulting whisky tasted quite different from the island's distinctive malt.

Most of us perceive water as being either hard or soft, characteristics which experts like John Hamilton can detect, not by taste, but touch.

Soft water, such as rain or river water, is more or less free from calcium and magnesium salts. Hard water, on the other hand, contains dissolved quantities of mineral, especially calcareous, salts. It is notoriously difficult to produce lather from soap in hard water.

'Some years ago, I was in Pakistan, on the North West Frontier, looking for sources of water suitable for bottling,' he says. 'In one particular stream, someone was washing clothes, so I didn't want to taste the water. I tested it by running it between my fingers. Hard water leaves a stickiness on your skin as it dries. Soft water tends to polish your fingertips. I confirmed it by borrowing some soap from the man washing clothes and working up a wonderful lather - a sure sign of soft water.'

Scottish water is predominantly soft, John explains, and contains very little iron. What makes it distinctive is the fact that it is lightly mineralised - so much so that, in many places, it is almost straight rainwater run off.

Within this, however, it does vary in character to experts like John, or Master Blender Robert Hicks. On more than one occasion, Robert has nosed tap water and rung the water company to tell them the chlorine content - normally one part per million - has increased slightly.

As water provides the medium for every stage of whisky-making - from the rain to make the barley grow to malting, trace elements to help the enzymes during fermentation, distilling and reducing the matured cask whisky to its bottling strength - a distillery's choice of supply is of paramount importance.

There is no doubt that particular water sources contribute their own individuality to whisky. Laboratory Services Manager Denis Nicol, one of Ballantine's in-house scientists, once conducted gas chromatograph tests on Islay whiskies and found the contribution of water to be very noticeable.

'The stream of aromas was split,' he explains. 'One branch was channelled into the chromatograph, the other into my nostril. For 40 minutes, I sniffed peaks of aroma coming off the whisky - and the smells were remarkable. Apart from smells you would expect, like heather and spagnum moss, there was peppermint which came from the Bog Myrtle, a plant which grows in boggy conditions. There was also the smell of Yellow Flag, a plant which has phenolic notes when the root is broken. All grew naturally in the water supply and together made up the taste of Laphroaig and the other Islay malts I was testing.'

But even though the flavour of the water is natural and linked to the eco-climate and the geography of the area, it has to be closely monitored. One hot dry summer, Laphroaig's water supply acquired an algaeic bloom from a pond weed which gave the whisky a minute off-odour.

'After consulting Glasgow University Botany Department, I introduced 200 Chinese Grass Carp to the dam to graze on the weed and the problem was solved,' Denis recalls.

His experience working with water supplies for distilleries reflects Ballantine's view of the importance of water to every stage of the whisky-making process. 'It is absolutely vital,' Denis says. 'Every water supply will leave its distinct mark on whatever whisky it is used to create.'

The view is reinforced by the long experience of John Hamilton. 'One well-known whisky, which I won't name, has a certain bitterness to the taste which can originate only from its basic water feedstock,' he says. 'Islay whiskies have an almost medicinal aftertaste, whilst Speyside malts leave a clean taste on the palate - all factors which, I am sure, are linked to the nature of the water.'

Just as the whisky map is divided into distinct regions, Scotland's geology falls into broad areas, too. Curiously, a connection exists between them which defines the nature of individual distillery water.

The Central and Lowland areas, for instance, are essentially a huge region of permeable sandstone acting as a sponge to soak up rainfall. The sandstone filters the water, which also picks up natural bicarbonates from the rock, before delivering it up in springs and streams. Further north into the Highlands, geological formations are composed of ancient volcanic rock.

'Fractured basalt, to be precise, which gives an element of filtration, but not as much as sandstone,' John explains. 'Highland water is effectively rainwater run off. When it comes out of a spring it is very close to rain, with some undissolved organics, and very soft.'

Interestingly, Speyside, which produces malts special enough to define it as a whisky region separate from the Highlands, also has its own peculiar geology. In this case, pre-Cambrian rocks and coastal alluvium - millions of years' deposits of earth, sand and gravel left by rivers - interspersed with old red sandstone which filters rainfall. At one time, this part of Scotland was tilted and Speyside was covered entirely by sea. Gravel beds extend as far north as the ski resort of Aviemore - evidence that much of Scotland was submerged a million years ago.

Gravel filters the water, enabling the purest supplies to leave their mark on important constituent malts of 17 Years Old, such as Glendronach, Miltonduff, Glenburgie and Balblair.

The renowned geologist Professor A.K. Pringle, who held the Chair in Geology at Strathclyde University, once gave up his summer holidays to bore for water around Miltonduff to ensure the distillery's precious supplies were maintained.

'He drilled down 270 feet without once hitting rock,' recalls former General Manager of ADL malt distilleries, Bill Craig. 'It was sand and gravel all the way. This undoubtedly had some bearing on the quality of our supplies.'

'I think there is something in the gravel filter theory,' agrees Balblair distillery manager Jim Yates. 'All the fields around here, and my own garden at the distillery, are full of round stones, smoothed thousands of years ago by water. One field next to the distillery has so many of them that it literally turns white when it is ploughed.

'Our water is drawn from a burn, but I think the original source is an underground spring. It has a certain amount of peat in it - the burn sometimes runs red after heavy rain. The water is exceptionally pure and the peat lends a subtle flavour to the whisky, making it very distinctive.'

Islay is geologically different again, with complex rock formations that change with the differing nature of the whisky on the island. In general, Islay water is close to natural rainwater. However, it runs through peat which once had a high seaweed content, giving it a medicinal flavour. As the island's geology changes, so does the nature of its water - and the 'personality' of its whisky.

'Bruichladdich, for instance, is perhaps the least distinctive in character of Islay malts,' John Hamilton believes. 'It is the most westerly distillery in Scotland, drawing water from a local reservoir in the hills. I am convinced its character is connected to its position and its water supply. Laphroaig, for example, on the south side of the island with a change of geology, has a completely different flavour.'

Master Blender Robert Hicks agrees. 'Some of a whisky's flavour can come from the water,' he believes. 'Anyone who has been on Islay, for instance, and seen the way peat colours the water will understand that the influence does come through.'

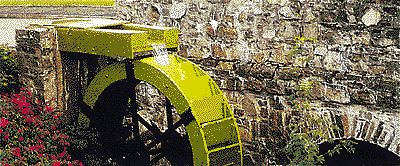

Some distillery water sources rise in nearby hills from springs that are quite difficult to find. A lade, or water course, is cut down to the distillery to ensure a good volume of supply.

But how were some of these obscure springs discovered in the first place? Scotland has a long and ancient tradition of water divining, or dowsing, often handed down within families. Armed with a forked hazel twig, metal rods or nothing more than an outstretched hand, the dowser can locate pure water hidden deep beneath the rock.

Alaistair Ballantine, a Fife water diviner and member of the Scottish Dowsers' Association, inherited the skill from his grandfather. 'He was a water diviner who used whalebone rods, but could also detect water without anything,' he says. 'He got all his family to try it out, so I have known I could do it since I was four years old.'

Water diviners were once widely used in Scotland and their skills are currently being rediscovered. 'The jobs I do range from domestic supplies to agricultural irrigation and fish farms where they need fresh water for the hatcheries,' Alaistair says. 'There is absolutely no doubt that divining played a big part in detecting the original water source for distilleries centuries ago.'

When distilleries were originally sited, a prime requirement was continuity of supply, followed by a water source with as little dissolved material as possible, vegetable or mineral, to make distilling easier. Other factors were taken into consideration, too. Local legend often pointed to a particular supply as being exceptionally pure or good for whisky-making.

Miltonduff distillery, in the heart of the Speyside area, lies near the ancient priory of Pluscarden, where monks brewed ale acclaimed as the finest in Scotland. For centuries, their sacred water source was the Black Burn, from which the water for Miltonduff single malt is drawn. The decision to use it for whisky is directly linked to the day the Abbot of Pluscarden Priory waded into the waters of the burn and blessed them, pronouncing them to be 'waters of life'.

At Balblair, in the northern Highlands, the outlook was decidedly less spiritual. This was an area teeming with illicit stills when whisky-making was forced to take to the hills. Balblair's unique, creamy flavour is owed in part to drawing water from a burn, The Auld Draeg, four miles from the distillery. Anyone who goes to such lengths to secure legal rights to water every metre of the way must be sure they are getting something special.

While most Speyside malts, like Glenburgie, rely on water from local hillside springs, other distilleries prefer to draw their supplies from lochs. Among them is Pulteney, made from the waters of the Loch of Hempriggs, one of the most northerly mainland lochs in Britain.

Ardbeg, the colour of pale, golden straw, stands on a lonely site at the water's edge on the south coast of Islay. Its water supply is taken from two lochs, Arinambeast and Uigidale, in the hills above the distillery.

The malts of 17 Years Old are carefully selected for their wide range of flavours, including the influence of their water, to create a perfect balance.

Even though Scotland has an abundance of pure water, distillers are careful not to waste any. Whisky's ingredients are all natural and it is in their interests to respect the environment. Even afterwards, when water has been used for creating the wort and wash and cooling the worm, it is put to a variety of uses - from heating greenhouses to grow the distillery manager's tomatoes to keeping tropical fish, warming the village swimming pool and even breeding eels. At Laphroaig, warm surplus water is pumped into the sea, attracting large numbers of fish and basking seals around the distillery.

Water has always been regarded as an element of mystery whose nature changes from place to place. It is similar only to the pot still in the way its character can influence the finished flavour.