| / WHISKY |

Leeze me on thee, John Barleycorn,

Thou king o' grain!

Scotch Drink

Robert Burns

The sheaf of barley occupies the first quarter of Ballantine's coat of arms because ripe grain represents the beginning of the process of making whisky. In the beginning there was barley - an ancient bond of man and nature.

Centuries ago, whisky-making was closely tied to the seasons. It took place in the colder months when live yeast was easier to handle and barley did not germinate so quickly. When summer came and temperatures rose, whisky-makers closed down their stills and returned to farm work or fishing.

Curiously, it was precisely this seasonal cycle that led to the establishment of Ballantine's maltsters, Robert Kilgour & Sons, perhaps the greatest technical experts on barley in the industry.

Back in 1875, Robert Kilgour was master of a small fishing fleet in the small Fifeshire coastal village of West Wemyss. Icy North Sea storms often confined them to harbour in winter, leaving crews with time on their hands. Kilgour set up a small malting plant in nearby Kirkaldy to keep his men occupied and provide year-round employment. However, the maltings soon proved more profitable than fishing and Robert's sons joined the business.

'Kirkaldy was ideally situated for a malting plant because Fife and the adjoining counties of Angus and Perthshire are renowned for the quality of their malting barley,' says Kilgour's Production Director Hector Cameron Page, better known as 'Ronnie' to everyone in the industry.

Kilgour's, with Ballantine's name proudly on its towers, has developed a formidable reputation for quality. A farmer who recently sent a load of grain for approval nervously asked the driver: 'Where exactly do Kilgour's take the sample from?'

'All over the wagon,' the driver replied.

'But that's not fair!' the farmer protested.

To ensure that whisky is always at its best, only the finest barley is used - and nothing is left to chance. Kilgour's breed their own seeds of many varieties, supply them to the farmer, inspect them regularly as they grow, then buy back the harvested barley for malting, leaving no room for error.

'Varieties of barley keep changing because we have to continually cross-breed the seed to keep it disease-resistant,' Ronnie explains. 'At the moment, distilleries use Prisma and Chariot varieties. Before that, it was Riviera and Tankard and the previous generation was Corgi and Golden Promise.'

Some malts stick to a single variety of barley, such as Golden Promise, convinced it influences the flavour of the finished whisky. Ronnie Page, who has studied barley closely since he joined Kilgour's as chief chemist in 1961, is doubtful.

Ronnie is chairman of the Institute of Brewing's Micro-Malting Committee, an important working party in the whisky industry which takes small half-kilo batches of new seed varieties and test-malts them to determine which will go forward to the following year. Time and patience are necessary for new seed development. The whole process of developing a new seed, with all the right qualities and a high alcohol yield, takes around 12 years from the first cross-pollination to becoming commercially viable.

'In the first six or seven years many varieties are eliminated,' Ronnie explains. 'Some people send them to New Zealand to speed up the process because they have two crops a year there. This is not always a good thing to do because the variety may be susceptible to a British disease and you wouldn't be aware of it.'

By years seven and eight, promising varieties are narrowed down for what are known as National List trials. 'At this stage,' Ronnie says, 'you could have as many as 30 varieties coming through, out of an initial 300-500 varieties, which might be made up of 30-40,000 individual seeds. This drops to around 15 and then falls further to perhaps eight as they are eliminated. After years of work, maybe only two varieties will survive the trials as commercially suitable.'

As the sifting takes place, Kilgour's select up to five tonnes of promising stock and sow it in two or three fields to make test maltings. Such care is taken because Scottish barley is considered the world's best for whisky-making - and that is not misplaced national pride.

'The maritime climate here produces good yields,' Ronnie explains. 'We grow grain that is well-filled with more starch to obtain more alcohol per tonne. The barley is better than, say, English barley from the south, because we have a shorter growing season in the north and everything has to develop more quickly. In a shorter season, the starch in the grain has to feed the shoot until it pushes through the ground. Then, photosynthesis produces sugars which enable the plant to reach the flowering stage.

'At this point, sugar that is not required goes into the head for the seed. Because of the short growing season, enzymes have to convert the sugar to starch very quickly. Good varieties produce lots of enzymes to push the process quickly. When whisky is made, the enzymes reverse to convert starch back to sugar. When yeast is added, the sugar is converted to alcohol. This is why northern barleys have more enzymes than southern varieties.'

The Scottish climate plays a vital role, too. 'You need the wind at certain times for the moisture in the air,' Ronnie explains. 'You need the correct amount of sunshine and also rain at the right time. However, if they all come in the wrong order, you've had it.'

Ongoing research by Kilgour's in conjunction with colleges of agriculture have helped develop barley seeds genetically designed for whisky. Centuries ago, when barley was closer to the wild, grain would have looked quite different, with a thin appearance.

Selective breeding has resulted in plumper seeds with shorter stems, or straws, which do not swing as much in the wind and are less likely to be damaged by storms. One effect of the customising of barley is that there has been a shortage of good straw which, of course, is made from the discarded stems. Now, experiments are taking place to bring back some of the older varieties with longer stems to provide straw for the farmer to sell.

Kilgour's not only provide the finest barley for the single malts that make up Ballantine's 17 Years Old, they also offer a complete service to the farmer, from lime and fertilisers to keep the soil in good condition to the best seed varieties to ensure maximum yields.

'When the seeds are growing we go round the fields once a month in the early part of the year,' says Ronnie. 'Nearer harvest time we inspect crops once a week to check for disease and general growth.'

The cycle of seasons still governs this aspect of whisky production. In August and September, farmers harvest the barley which is brought in convoys of wagons to Kilgour's. More than 43,000 tonnes are collected in just under five weeks to provide stock for making whisky for the coming 12 months.

'We used to bulk-buy some of the barley at harvest time and more in January-February. The problem was that the grain in January-February tended to be lacking in energy and didn't achieve the results we expected in malting.'

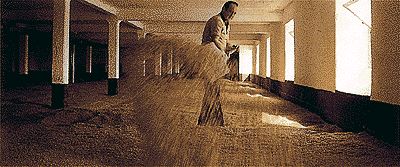

By buying a year's stock at once, Kilgour's can dry the grain and control humidity precisely with a range of sophisticated equipment. The malting done by Kilgour's is a mechanised version of skills which have been practised for centuries. In a handful of single malt distilleries, such as Laphroaig and Glendronach, malting is still carried out by hand, turning the grain slowly with broad shovels, instilling fresh air to it, before drying it in aromatic peat smoke to stop germination.

Despite the modern technology used at Kilgour's, the principle is still the same as for the traditional method. The old skills of hand and eye are relied upon heavily. 'You still need to rub the seeds between your hands and watch the process carefully as it happens. Your eye can tell you something much quicker than drying a sample and sending it to the laboratory to have it checked.'

After supplying seed and carefully supervising its growth, Kilgour's take delivery of the full, ripe, harvested grain, fresh from the fields with a moisture content of around 22 per cent. Vertical driers at the maltings reduce this to around 12 per cent, making the barley dry enough for storage. During the eight weeks it lies in store, it is frequently aerated to wake it from dormancy and activate the life in the seeds.

After resting, the barley is transferred to steeping tanks where it is soaked in water for up to 60 hours and rigorously checked for quality. Here, it absorbs up to 45 per cent moisture. The water is changed and compressed air blown through it, like a jacuzzi, to keep the barley on the move. The mixture is then pumped into a Saladin Box (named after its French inventor), which has a perforated floor through which the water drains, leaving the moist barley. In old-style distilling processes, damp seeds are spread on the stone floor of the distillery.

Humidity and temperature levels are rigorously controlled because it is here that nature starts to work the first of her miracles. The seeds begin to grow shoots, or acrospires, at one end and tiny rootlets at the other. In the process, they release enzymes that convert the starch into malt sugar as the grain begins to germinate. To ensure even drying, sprouting and airing, the barley is continuously turned.

After four or five days, germination has to be halted to capture the malt sugar and an enzyme called 'diastase', responsible for making the starch soluble. If the seeds were allowed to grow for too long, the main stem of the barley would begin to emerge, spoiling it for distillation.

The 'green malt', as it is now called, is controlled very carefully at this point. The precise moment at which germination is halted is crucial - a classic example of experience, judgement and instinct combining with science to obtain optimum quality.

This takes place in the kiln, where the green malt is spread on wire mesh and dried over a peat fire. As the aromatic peat smoke permeates the grain, the drying malt absorbs its distinctive flavours, helping to give the finished whisky its individual characteristics.

'When people think of heavily peated, medium or lightly peated malts, they often make the mistake of associating Islay malts with heavy peating,' says Ballantine's Master Blender Robert Hicks. 'Laphroaig is an example of a heavily peated Islay malt, but within Islay you have medium and lightly peated whiskies.

'There are two styles of peating - Islay and Mainland. Islay has an iodine, almost disinfectant-like flavour because thousands of years ago the peat was seaweed-based, containing a form of iodine, and this comes through. Mainland peats are based on flowers and shrubs and, while you get a flavour of smoke, quite a lot of floral smell is associated with them.

'Contrary to popular opinion, you can actually get Islay malts lighter in peat than Mainland malts. They are simply two different styles. We use both in 17 Years Old, from heavily peated malts to completely unpeated Lowland whiskies. The important thing is to achieve the right balance - and this is where the skill of making 17 Years Old lies.'

Back in the kiln, meanwhile, the peat smoke in the flow of warm air reduces the moisture of the green malt from 48 per cent on loading, down to as little as 3.5-4 per cent on 'stripping' (the final stage of drying the malt), the point at which it is removed from the kiln.

The cured malt is then stored in malt bins for approximately six weeks before being screened prior to despatch to the distilleries. The screening process removes the rootlets which are now known as 'malt culms'. This is the only by-product, which is pelletised before despatch to compounders for inclusion in animal feedstuffs.

The cured malt is weighed off into vehicles and transported in bulk to the distilleries. There, the alchemy of making fine malt begins in earnest. The malted barley, the first of the ingredients of whisky portrayed on Ballantine's coat of arms, combines with the next element of water on the crest as the ancient art of distilling gets under way.