| / WHISKY |

From scenes like these, old Scotia's grandeur springs

That makes her lov'd at home, rever'd abroad

The Cotter's Saturday Night

Robert Burns

Imagine a life when winters were so harsh that survival was uncertain. Terrain so rugged that the shortest journey took several days. Homes vulnerable to marauding bands who stole cattle and destroyed whole communities. For centuries Scots endured a wild landscape, warring families, invasion by the English and systematic attempts to destroy their culture. Small wonder their character is hallmarked by fierce independence and a will to survive.

In such an uncertain existence, durability was prized. The warmth of woven tartan, the secret of making whisky to sustain the body through long cold journeys or battle, and, above all, the protection and close community of the clan system.

From these roots grew Scotland's unique cultural heritage. Though constitutionally tied to Britain, Scotland retains its separate legal structure, education system, banknotes, heraldry, Gaelic language and ancient sports featured in the Highland Games.

Until 1603, Scotland was a sovereign state with its own monarch and parliament, but in that year the Scottish king James VI ascended the throne of England. After being crowned James I, he joined the two countries to form the basis of the present government system, though full union was not achieved until 100 years later.

In recent years, there have been increased calls for greater Scottish autonomy, ranging from more say in decision-making to complete political independence from Britain.

This national pride and independence of spirit has its roots in the unbreakable bonds of blood and loyalty demanded by the ancient Clan system. The word clann originally meant children. Clans were communities sharing the same ancestry, blood ties and family name who lived together in the same area. Among them, names such as MacGregor, Bruce, Campbell, McDonald and Stewart passed into the pages of Scottish history. Each clan member swore loyalty to his clan chief who, in turn, pledged to fight on behalf of the weakest family member.

Scottish history is full of heroic stories of clans combining to fight courageously the English. In truth, it was tartans and badges that were important for identity because, much of the time, clans did battle, not with invaders, but each other.

'They fought each other tooth and nail,' explains Harry Lindley, retired director of Kinloch Anderson of Edinburgh, Scotland's premier kilt-makers. 'Many feuds and disagreements were over stolen cattle or sheep.'

The clans traditionally chose to identify themselves by using local shrubs, sacred plants and flowers as badges. The House of Bruce, for instance, wore rosemary; Clan Hamilton bay leaves; and Matheson clansmen a four-petal rose. They were attached to the brim of the knitted bonnet or tied around the arms as insignia. Some had medicinal properties, but plants were more usually chosen as badges because they grew commonly in the territory of a particular community.

Scotland's own plant badge, the thistle, first appeared on silver coins in 1470. There is no evidence to support a popular legend that an invading Viking stepped on a thistle and cried out, giving Scots warning of an attack. But, curiously, the Latin motto nemo me impune lacessit (roughly translated as 'no one attacks me and gets away with it') is usually associated with the Scottish thistle badge.

Clan members wore their own clan tartans. They were both practical everyday wear against the weather and a proud uniform representing the family to which you belonged, or were linked.

Today's ceremonial Highland regalia includes remnants of the clansman's readiness to fight. The outfit comprises the belted plaid (tartan fastened by a belt); garters, usually scarlet and tied with a special knot, called in Gaelic snaoim gartain; a jacket or doublet; low-cut shoes (black or brown brogues are the correct daytime wear with red-based tartan); and on special ceremonial occasions, a small armoury of weapons.

These usually consist of a claymore sword with a basket hilt lined with scarlet; a dirk kept in the waistbelt; a dagger, or sgian dubh, in the stocking; and a single-barrelled muzzle-loading antique pistol in the belt. A powder horn is worn on the right side, with the mouthpiece to the front in readiness.

Clansmen went into battle to the rousing sound of the bagpipes, which have been used as military instruments, and for clan gatherings and laments, since before the 16th century. Although bagpipes can be found in several countries, powerful, richly-toned Highland pipes are the most widely played bagpipes in the world.

The Gaelic word for tartan is breacan, meaning chequered, and describes the check-like arrangement of tartan patterns. Early tartan was produced from materials found locally on clan territory. Early weavers and dyers were restricted by methods and materials they had to hand.

'Back in the 1600s, the lady of the house did the spinning, while the father worked the loom, weaving in the back of the bothy where the light was not very good,' says Harry Lindley - a prominent tartan designer, member of the Heraldry Society and an expert whose wisdom has helped identify many ancient fragments of Scotland's traditional cloth.

'The wool was coloured with local dyes found in nature. If you wanted a shade of lilac, for instance, you pressed it from elderberries. Black, which wasn't true black, came from elder bark or a blackberry with young shoots.

'Meadowsweet was used to produce a darkish grey, while fawn or light brown came from lichen. They developed yellow from birch leaves, onion skins, the common dock plant or sometimes bracken roots.

'Blues came from ivy berries, whortleberries or berries cut from privets. For reds, they used the inner bark of the birch or the common sorrel plant. Purples were obtained from damson fruit.

'The technique was more or less the same for all of them - plants, bark or berries were boiled and stirred like porridge. Dyes were made fast with salt and the finished cloth washed in the burn to remove any surplus. The finished tartan had a faded look, compared to the vibrancy of modern aniline dyes. Old tartans rarely had strong colours; they would tend to merge with each other.'

The kilt most commonly worn was the Belted Plaid, wrapped skirt-like around the waist and secured by a belt, with the surplus slung over the shoulder, where it was secured by a brooch, and left to hang down the back. The belted plaid, or Breacan-feile, was made from a length of warm, heavy cloth. So all-enveloping, in fact, that the old question of what a Scotsman wears beneath his kilt remains a mystery to many.

Not, of course, to Harry Lindley. In fact, the master of the kilt is quite open about it. 'The answer's simple,' he says. 'When a Highlander put on his belted plaid, he wore nothing at all underneath it.

'The only exception was a cotton tunic, like a modern T-shirt. A lot of cotton and linen was woven in Scotland, and laid out on hillsides to bleach in the sun. Over a tunic he wore a waistcoat made from deerskin with the hair left on to retain the warmth.

'The traditional belted plaid was quite long, about four or five metres. Along with the belt securing it, Highlanders wore a pouch, or sporran, to carry important items. One was money - if the wearer had any - and oatmeal to sustain him. On a long march, he could take a handful, moisten it in a burn and eat as he went.'

The contents of a sporran, apart from money and food, may have included a quaich, from the Gaelic for 'cup', a small two-handled wooden vessel for taking whisky.

Tough Highlanders needed the warmth and invigoration their whisky provided. It was once the practice, for example, for roaming warrior clansmen to dip their plaids in icy water and wrap the soaking cloth around themselves before settling down to sleep in the open. As the water froze, it formed a cocoon of solid ice to protect the sleeper from the bitter Highland winds.

Whisky was a welcome part of the painful thawing-out process. Highlanders would have used the quaich from their sporrans to warm themselves with a dram. Legendary warrior Rob Roy, who followed this kind of spartan lifestyle, is said to have existed mainly on a diet of 'whisky chuckies' - balls of oatmeal soaked in whisky.

By the 1700s many clan chiefs, sophisticated and educated in France, commissioned silver, pewter and gold quaichs engraved with Celtic patterns, for their own use.

The Scotch whisky industry maintains the tradition with The Keepers of the Quaich. 'The Keepers', as they are known, are an exclusive society founded by leading Scotch whisky distillers - Ballantine's was a founder member - to honour those who have promoted the nobility of Scotch whisky. Among its patrons are clan chiefs from great Scottish families whose histories date back to the beginning of the Scottish race.

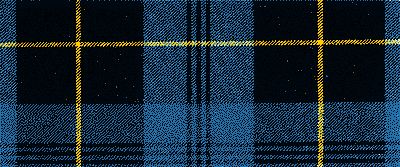

Harry Lindley was asked to design a tartan in 1986 for The Keepers of the Quaich in celebration of whisky. 'The background is blue, representing the water of life. The barley is depicted by a yellow line and there is a brown tone for peat - the colour of the water, especially on Islay and Orkney,' explains Harry, who was recently made an Honorary Keeper.

The Water of Life Whisky played a vital role in Scottish daily life, but little is known about the earliest days of distilling. The spirit now enjoyed in 200 countries was first known as aquavitae, the 'water of life'. In Gaelic, the ancient language of Scotland and Ireland, it became uisge beatha, later usquebaugh.

To the ears of occupying English soldiers of Henry II, in the 12th century, the pronunciation sounded like uishgi. And so, in time, it became 'whisky' - without an 'e', it should be noted. 'Whiskey' belongs to the Irish and Americans while the flavour, they say, belongs to Scotch.

The earliest written record of distilling was made 500 years ago, when a clerk carefully inscribed in the Rolls of the Scottish Exchequer in 1494: 'eight bolls of malt for friar John Cor, wherewith to make aquavitae.' A 'boll' was a measure of grain equivalent to six bushels, or 25.4 kilograms. Friar John's identity is a mystery.

Whisky sipped from a quaich carried in the sporran was widely believed to have medicinal qualities. So much so that, in 1505, the Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh was granted power to supervise its production. In 1636, the Worshipful Company of Distillers was set up by doctors to exercise similar control in England.

One of the oldest cures for an upset stomach is Highland Bitters, consisting of herbs and spices mixed with whisky. A dram of neat whisky before a meal is a popular precaution against stomach upsets caused by change of diet when abroad. Hot Toddy - whisky with sugar or honey and hot water - is universally regarded as a soothing relief for the common cold. And physicians acknowledge that a small daily dram can be beneficial for patients with poor circulation.

Whisky, like the tartan and the clan system, has played a dynamic role in Scottish history, helping to build the nation, shape its traditions and mould the proud, determined character of its people.

'Most observers agree that the Scottish tradition of whisky drinking can be attributed to the Celtic love of conviviality,' explains Ballantine's Hector MacLennan.

All life's milestones, from cradle to grave, were celebrated in whisky. A dram was provided for midwives at births, for christening and betrothal feasts and at every wedding. A glass of Scotch would be raised to celebrate the building of a new home or the safe arrival home of fishing boats.

'The greatest occasion of all was - and indeed still is - the Scottish funeral,' adds Hector. 'The spirit of the departed was believed to linger through hospitality between relatives and friends.

'"For God's sake, give them a hearty drink" were the last words of a dying Highland laird to his son. It was considered an insult to the dead if funeral guests were not given an abundance of whisky. It was not surprising that English officers who witnessed such occasions pronounced a Scottish funeral to be merrier than an English wedding.'

With the extended families embraced by the clan system, it would be considered something of an insult if less than 800 litres were consumed at a big funeral, Hector adds. These occasions could go on for several days and were often quite spectacular.

'The hospitality dispensed by a well-known clan chief, Forbes of Culloden, at his mother's funeral was lavish. The funeral procession took place at night with flaming torches and bagpipes - a wonderful sight. However, when the mourners finally arrived at the grave, they found the corpse had been left behind. But then, Forbes of Culloden owned his own distillery!'

Scottish hospitality is legendary. As early as 1498, the Spanish Ambassador to Scotland reported home that, 'The Scots like foreigners so much that they dispute with one another as to who shall have and treat the foreigner in his house - nothing in Scotland is scarce, but money.'